Testing randomness

While deep diving into the code I very often see people struggle when testing random changing/things. There is a really simple solution for this and in this blog post, I’m going to show you "one simple trick" that will fix this problem.

tl;dr - Use dependency injection. Inject source of changing data from the outside and make it return a fixed value. Voilà it is done.

Let’s start with something simple - time. Every time you check it, it will be different. Even if your precision is like a second, minute or even a day there will be a time when your tests will fail because they’ve been executed at the wrong moment. To avoid looking for too far-fetched example let’s say you need to implement a time-limited discount for a product.

import java.time.Clock;

import java.time.LocalDateTime;

class DiscountService {

private final Clock clock;

DiscountService(Clock clock) {

this.clock = clock;

}

public boolean isActive(Discount discount) {

final LocalDateTime now = LocalDateTime.now(clock);

return discount.startDate.isAfter(now) && discount.endDate.isBefore(now);

}

static class Discount {

private final LocalDateTime startDate;

private final LocalDateTime endDate;

Discount(LocalDateTime startDate, LocalDateTime endDate) {

this.startDate = startDate;

this.endDate = endDate;

}

}

}And the simple test for the above class:

public class DiscountServiceTest {

private final long nowMilliseconds = 1521056135184L;

private final Clock fixedClock = Clock.fixed(

Instant.ofEpochMilli(nowMilliseconds),

ZoneId.systemDefault());

private final LocalDateTime now = LocalDateTime.now(fixedClock);

private final DiscountService discountService = new DiscountService(fixedClock);

@Test

public void should_be_inactive_when_before_start_date() {

final LocalDateTime tomorrow = now.plusDays(1);

final LocalDateTime dayAfterTomorrow = tomorrow.plusDays(1);

assertFalse(discountService.isActive(new Discount(tomorrow, dayAfterTomorrow)));

}

@Test

public void should_be_inactive_when_after_end_date() {

final LocalDateTime yesterday = now.minusDays(1);

final LocalDateTime dayBeforeYesterday = yesterday.minusDays(1);

assertFalse(discountService.isActive(new Discount(dayBeforeYesterday, yesterday)));

}

@Test

public void should_be_active_when_after_start_and_before_end_date() {

final LocalDateTime yesterday = now.minusDays(1);

final LocalDateTime tomorrow = now.plusDays(1);

assertFalse(discountService.isActive(new Discount(yesterday, now)));

}

}This is really simple you might say and you are sure that it is not worth the trouble. Well, maybe it isn’t maybe it is? How long will discount last in a leap February, are you going to wait until February in next two years to check it? How are you going to verify that complicated business logic based on current time works? How do you know if the scheduled job will be executed exactly when you need? What will happen with job executed on 30 th day of a month in February?

(Clock is for Java 8+ in older java versions we used to inject something which we called TimeProvider with method now() and it worked the same as a clock for time provider)

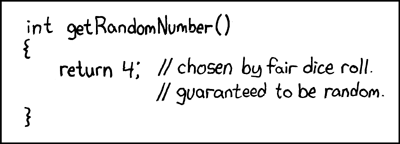

The same is with random stuff. Testing randomness might be even more tricky because when something is random it usually means that your decision depends on it (unless it is some kind of UUID used as a key which I also implemented with IdGenerator or something like this to avoid static calls ;)). How are you going to verify if your calculation for mage attack points works? You can either hope for the best or simply provide the source of randomness from the outside and make it return fixed value while testing.

class Mage {

static final int ATTACK_FACTOR = 5;

private int baseAttack;

public Mage(int baseAttack) {

this.baseAttack = baseAttack;

}

public int attack(Random random) {

final int attackFactor = random.nextInt((ATTACK_FACTOR + 1));

final int extraAttackPoints = attackFactor == 0 ? 0 : baseAttack / attackFactor;

return baseAttack + extraAttackPoints;

}

}Tests for calculating maximum and minimum attack points:

public class MageAttackTest {

private final int minAttackFactor = 0;

private final int maxAttackFactor = Mage.ATTACK_FACTOR;

@Test

public void should_have_at_least_base_attack_strength() {

//given

final int baseAttack = 100;

//when

final int attackPoints = new Mage(baseAttack).attack(fixedRandom(minAttackFactor));

//then

assertEquals(baseAttack, attackPoints);

}

@Test

public void should_have_up_to_20_percent_more_attack_strength() {

//given

final int baseAttack = 100;

//when

final int attackPoints = new Mage(baseAttack).attack(fixedRandom(maxAttackFactor));

//then

assertEquals(baseAttack + 20, attackPoints);

}

private Random fixedRandom(int number) {

return new Random() {

@Override

public int nextInt(int bound) {

return number;

}

};

}

}Sometimes you can not just inject something into a field of your class. Instead of doing some weird hacks to make it happen just inject fixed implementation as method parameter as I did above.

The solution is very simple, but very often I see LocalDateDate.now() called somewhere inside business method and I cringe every time because I’ve spent a lot of time to get rid of something like this (don’t ask it was long time ago…) to pinpoint and fix a bug which was time-related…

the code can be found on my GitHub

Image credits:

If you've enjoyed or found this post useful you might also like: